In which the author, a 54 year old with 30 years in the field of mathematics education, takes the GREs, his first attempt at taking a standardized test in almost 30 years. Here is a list of the other posts in this series:

Part I: It’s Me vs. The Stinkin’ GREs, part I

Part III: High Security & Writing My Time

Part V: In Which I Experience a Freak-Out

With my brain running on empty after 4 hours of non-stop poking and prodding, I slid my chair back and attempted to stand and flee, but alas, the friendly folks at ProMetric were not having any of it: since this is the age of instant gratification, aided and abetted by the microchip, I would be immediately informed of my scores on the multiple choice section, which would be followed 10 days later by the scores on the written analysis section (which would be carefully analyzed by an experienced educator culled from an ad placed on CraigsList…)

I clicked on the next screen, where two numbers appeared on a blank field:

Verbal Analysis: 168

Quantitative Analysis: 159

Would you like to send your scores to an institution?

I shrugged my shoulders; yes, a 168 on the verbal analysis was not only passable, but pretty damned good, considering the scale goes to 170. The quantitative analysis was 2 points lower than I had scored on the home version, but then again, I hadn’t experienced the freakout that went on at the test center. Looking up the scores in the comfort of my home, I learned that I was in the 97th percentile in verbal analysis, but only 79th percentile for quantitative analysis.

So it became a “good news, bad news” sort of thing, and I’m sure the admissions people would put more weight on the verbal scores that on the math. After all, if I was going to pursue a PhD, wouldn’t it be more important that I can read and comprehend vast amounts of written information, or complete 30 irrelevant math problems in 35 minutes? I clicked “yes” and sent my scores on to CUNY. A few weeks later, my scores on the written section were delivered via email: 5.5 out of 6, which placed me in the 97th percentile once again. When I informed my friend Trisha of this achievement, she called me a “worthless bastard,” as she had “only” gotten a 5 out of 6 on the writing section when she took the GREs a bunch of years ago. Oh, and she’s a professional writer as opposed to hack like me.

So it became a “good news, bad news” sort of thing, and I’m sure the admissions people would put more weight on the verbal scores that on the math. After all, if I was going to pursue a PhD, wouldn’t it be more important that I can read and comprehend vast amounts of written information, or complete 30 irrelevant math problems in 35 minutes? I clicked “yes” and sent my scores on to CUNY. A few weeks later, my scores on the written section were delivered via email: 5.5 out of 6, which placed me in the 97th percentile once again. When I informed my friend Trisha of this achievement, she called me a “worthless bastard,” as she had “only” gotten a 5 out of 6 on the writing section when she took the GREs a bunch of years ago. Oh, and she’s a professional writer as opposed to hack like me.

Some Reflections on the Nature of Standardized Tests from Someone Who Did Quite Well…

I won’t know if I was accepted into the PhD program of my choice, and if this entire process was a waste of time and money, so be it. Here’s what I did learn from taking the GREs, and I’m sure nothing about what I’m about to say is going to surprise you.

Standardized Tests Are Mindless Bullcrap (and probably worse…)

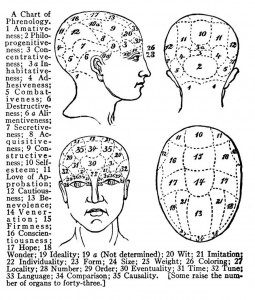

The current state of standardized testing…

There, I’ve said it, and now I’ll tell you why. As someone who is interested in mathematics and believes statistics can be a helpful tool to assess the proficiency and understanding on a mass scale, it is important to understand that for a test to be useful it has to be both valid and reliable. It has to actually assess what it says it will assess, and it has to do it in a way that the results will be pretty much the same no matter how many times it is conducted, free from outside influences. As a way to measure a group of people, it is probably valid and reliable, because the outside factors can be distributed over the many test takers. To get a portrait of an individual, it is clearly flawed, and probably no better than the 19th century practice of phrenology.

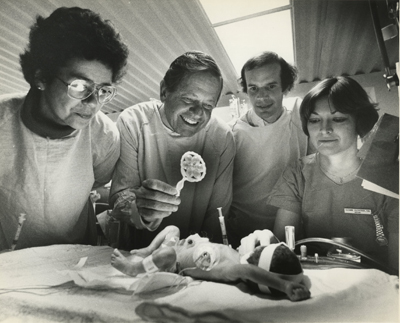

What can a pediatrician teach us about the usefulness of standardized testing?

From here, I’ll have to swerve a little bit to discuss the work of one of my idols, T. Berry Brazelton, whom I admire very much (except for the diaper commercial he made several years back…) In 1973, Brazelton released the “The Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale,” better known as the NBAS. It was a marked departure from previous tools for assessing newborns, as it was based on “capabilities” rather than “deficits.” The two main factors in performing a NBAS was that the baby had to be in “optimal state” and that the goal was to elicit the “best performance possible.”

“Optimal state,” meant that the baby being examined had to be calm and attentive; it made no sense to assess an infant who was “disorganized” because, as you can imagine, the data would not be valid. Brazelton’s goal was to obtain a true representation of what the infant is capable of doing, and this could only be done when the students are in an “optimal state.”

The second major philosophical basis for the NBAS was obtaining the best performance possible. That is, instead of giving the infant a single task and recording the result, the NBAS specifies that the subject be given the same task over and over again, and recording only the best performance. According to the Brazelton Institute website, the goal of the NBAS is as follows:

By the end of the exam, the examiner has developed a vibrant portrait of the newborn, which can be used to tailor caregiving to the baby’s specific physical needs and behavioral style.

If we substitute the word “newborn” and “baby” for “student,” “caregiving” with “teaching” and “physical” with “academic,” we have the basis of what a “good” assessment should actually do.

Can we really say that our assessment systems are designed to bring out “best performance” based on a subject’s “optimal state?” I think you’ll agree that this far from what our current standardized tests are designed to do: instead of creating assessments designed to accommodate each student’s individual backgrounds (which is not all that hard to do, given the current state of technology), we are forced to to contend with a “one size fits all” system that treats every student the same, irrespective of the student’s individual profile.

One of these students may end up in your classroom. Should he or she be given a standardized test after 6 months?

The result is that we have kids who come from clearly divergent backgrounds who are required to take the exact same exam. Do you have a 12 year old student who arrived in the US less than a year ago from a small town in Ghana and who is in his first year of education? Give him the test! Do you have a student who clearly suffers from untreated behavioral issues, including ADHD? Give her the test! Do you have a student who has been living in a homeless shelter for the past 2 years and has no place to study? Give him the test! Do you have a student who has a chronic illness that prevents her from attending school on a regular basis? Give her the test!

I can’t say whether my GRE score is representative of when I was in an “optimal state” and if it elicited my “best performance.” It was less a fair assessment of my actually skills and knowledge and more an indication of how I could sustain focus and attention while answering 4 hours worth of decontextualized and largely irrelevant questions. There must be better ways to find out what people know in order to judge their fitness, whether that be as a teacher or a learner. The current system gives us crappo information, devoid of any validity or reliability. Is this the best we can do in the 21st century?

Pingback: Title Bout: It’s Me vs. The Stinkin’ GREs, Part I |

Pingback: Me vs. the GREs – High Security and Writing My Time |

Pingback: Me vs. the Stinkin’ GREs: Test Day Arrives |

Pingback: Me vs. The Stinkin’ GREs: In Which I Experience A “Freak-Out” |